By Elifelet Sara Lavie

The current 17-day digital blackout in Iran is not merely a “disruption of service.” Sociologically, it represents the transformation of a sovereign state into what Erving Goffman termed a Total Institution.

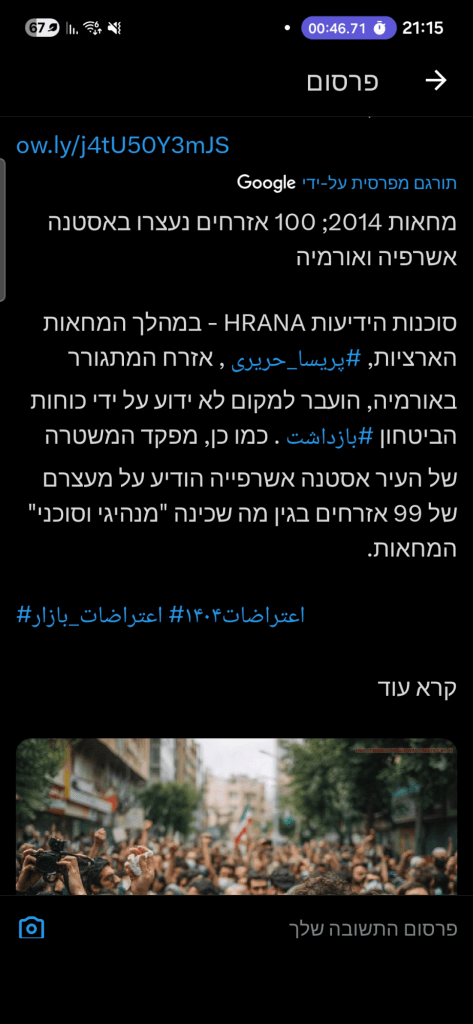

In a total institution—be it a prison, an asylum, or the “sheltered” environments I study in my thesis—the state enforces a breakdown of the barriers between the private and the public. By severing the internet for 92 million people, the Iranian regime has effectively “institutionalized” its entire population, exerting a monopoly over the perception of reality itself.

1. The “Stripping Process” of the Digital Self

In Goffman’s analysis, the “inmate” undergoes a mortification of the self—a systematic stripping away of their identity and their ability to present themselves to the world.

During this blackout, the Iranian citizen is stripped of their digital “front stage.” When we see accounts like @ourlittlewavves noting that “mostly Iranians themselves” are posting in English to break the silence, we are witnessing a desperate struggle against this stripping process. Without a digital presence, the protester is reduced to a state-controlled category: the “rioter,” the “agent,” or the “terrorist.”

2. The “Minneapolis” Tactic: Semantic Terrorism

While the citizens are silenced, the regime’s mouthpieces use the global “front stage” to engage in Semantic Terrorism.

Take the recent tweet from Seyed Mohammad Marandi, who used the phrase “The Holocaust in Minneapolis” over a picture of a shoe bin to describe American domestic unrest. This is a textbook case of Rhetorical Inversion. By appropriating a term of ultimate historical trauma like “Holocaust,” the state performs two acts of linguistic sabotage:

Normalization: It drains the word “Holocaust” of its specific gravity.

Deflection: It attempts to rebrand the Iranian regime as a “humanitarian observer” of Western atrocities, effectively neutralizing the West’s moral authority to criticize the violence in Tehran.

3. Foucault and the Panopticon of Silence

Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish suggests that power is most effective when it is invisible but the threat of surveillance is constant. The blackout creates a Semantic Panopticon. The state doesn’t just hide the truth; it makes the “truth” linguistically impossible to express.

When a 67-year-old war veteran like Mohammad Khan-Mohammadi is killed by state forces, the blackout ensures the state has the first and final word on the “meaning” of his death. Through Hermeneutic Terrorism, the “Veteran” is re-coded as a “terrorist,” and the “Protest” is re-coded as a “Foreign Plot.”

Conclusion: Refusing the Institutional Narrative

The danger of the total institution—whether it’s a sheltered factory or a country under a firewall—is the “enforced silence” that is framed as “security.”

Semantic terrorism thrives in the dark. It relies on our willingness to let our vocabulary be hijacked. To resist, we must insist on the stability of our definitions. A protest is not a riot. A veteran is not a terrorist. And a 17-day blackout is not a “security measure”—it is a crime against the collective memory of a nation.

Leave a Reply